What makes TikTok unique?

A behavioral analyses of the leading social media app

I recently gushed to a friend about the intriguing new behaviors emerging on TikTok. He sagely pointed out that that’s only typical of any emergent social media. He is probably right. This got me thinking anyway - what about TikTok makes it a breakaway media app? Most deconstructions of TikTok’s success have focussed on the power of its algorithms. But I’m more interested in unraveling how its design drives novel user behaviors. So here goes.

Things people do using TikTok

For a tiny app sporting a small feature set, TikTok sure is many things to many people. Here’s a glimpse of what some user tribes have done with the app recently.

'For Lesbians, TikTok Is ‘the Next Tinder’: Young women feeling alienated by dating apps and bar culture are finding love on TikTok's ‘For You’ pages.

Trading activity on Dogecoin spiked when a TikTok challenge urging viewers to buy the cryptocurrency went viral. The meme-based coin's 24-hour volume surged above $878 million, a 683% increase from its average daily volume over the past year.

In a mass coordinated effort teenage TikTok users scooped up tickets to President Trump’s rally in Tulsa, leaving hundreds of seats empty.

Here’s a video discussing eating disorders on TikTok - trigger warning.

And here’s a video on how teens trumped Trump’s rally using Tiktok, ouch!

So who really is on TikTok?

TikTok is oftentimes written off as “Ah, that teen app”. But everywhere I see evidence that other age groups are active on it too. The first convincing WOM recommendation I got about TikTok was from an Asian person in their 40s. The person who started the campaign to boycott Trump’s Tulsa rally looks to be past their teens. Lesbian women of different ages seem to be connecting on TikTok. People trading in cryptocurrencies possibly cannot all be in their teens. And teens don’t feature in a lot of videos in the app.

Statistics from this year suggest teens make up around 40% of TikTok users, but its adult user base is growing. Food for thought.

Seeking ubiquity

Facebook’s design evolution shows how wickedly tricky it can be to scale a massive global platform. Scale then is much more than user numbers; it is about driving and supporting diversity in user behavior. The position such a platform vies to take - and hold - is ubiquity in the user's life.

There may be several paths to such ubiquity. Facebook’s approach: provide a growing palette of features to support lots of distinct user needs. TikTok’s approach: enable one core behavioral pattern that users can adapt to endless goals.

Further, such ubiquity can come from innovating in two product dimensions. One is spatial and the other temporal.

In the spatial dimension, Facebook’s approach is to remain multi-screen. It chooses not to ignore the desktop product in favour of mobile (note the recent introduction of 'dark mode' on desktop) . TikTok is instead focussed on mobile. It sees the handheld screen and mobility as its users' defining spatial conditions. This helps it reach and retain the widest, largest user base possible, as mobile is now the primary digital device globally.

In the temporal dimension, Facebook engages us in many different time-attention formats. Asynchronous messaging, long-form reading, scheduling and time management (calendar & events), photo and video sharing, buying & selling (marketplace), games and a lot more. Nothing seems to escape Facebook's temporal scope.

TikTok is hyper-focussed in the temporal dimension - short videos with music. By strictly restricting this depth of attention to a) one video at a time and b) a fixed number of seconds per video, TikTok ensures that users have a near-perfect expectation of how they will be engaged when they fire up the app. This removes an attentional unpredictability which users experience on Facebook. TikTok’s temporal format helps users focus fully on content, outcomes, and rewards.

At the risk of sounding vague, let me say this: ubiquity does not come equal, and it may mean different things on different platforms. TikTok’s ubiquity is very different from Facebook’s ubiquity. From the user’s perspective, I don’t see why these two cannot happily co-exist.

The making of memes

As its core, Tiktok may be a platform for memetic transmission. Its design as discussed above supports one behavioral pattern fully, and well: the fast creation, transmission and consumption of discrete micro-units of culture.

“Wait, doesn’t instagram do just that?” I hear you ask. Not really. To understand why, hear Richard Dawkins beautifully explain the concept of the meme in the video below.

Two key takeaways from the video above: memes spread by copying themselves, and they do this via means akin to natural selection. Simplistically put: the quality of the copy determines if it is passed on and earns a chance for further replication.

Notice how Instagram does not provide ways for content to spread through copying. Instagram has chosen deliberately not to include a repost feature, spawning a bunch of apps that do it for you. Instagram emphasises original content.

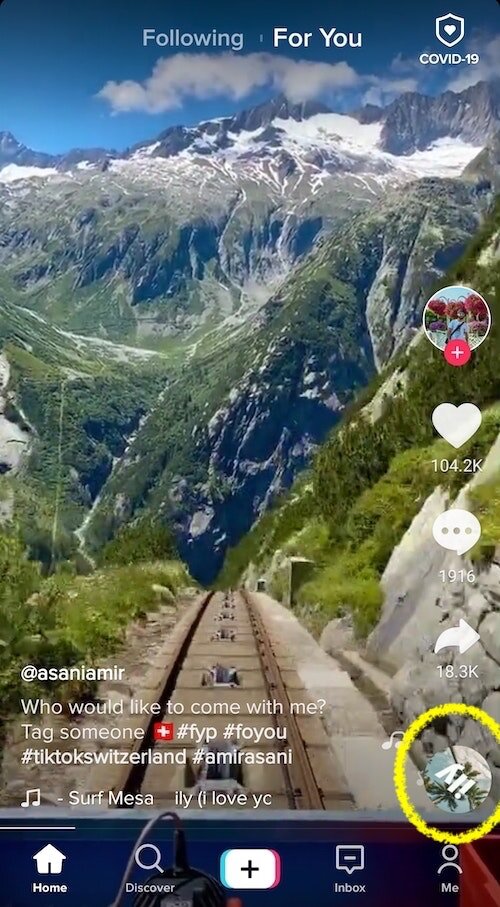

TikTok on the other hand actively encourages copying. The almost invisible little TikTok feature that allows endless adaptation of a video is ‘Soundtrack’ (highlighted at corner right bottom in image below). It is also the only animated feature on that UI so you almost can’t miss it.

This creates a self-reinforcing loop of copying behavior, and an endless stream of copies of the original video.

Primacy of the Idea

According to Dawkins, a meme happens when a unit of cultural information - an idea - gets replicated. The idea is primary to memetic transmission above all else. Not who replicated it, or when it got replicated. In contrast, context (not the idea) is central on Facebook. I suspect Facebook’s algorithm looks at contextual cues around an idea. Things like who posted it, who they are to you, when they posted it, who liked and shared it etc are crucial. TikTok’s algorithms may also optimise on these parameters. But I think its memetic mechanism drives the idea forward based on the merit of its content above all else.

Am I the only one seeing this difference as having massive implications? Hypothetically speaking: this fundamentally changes how the platform attributes meaning to content, and how it senses why users behave in the ways they do. For example, Facebook would understand the Boycott Trump Rally meme as shared by teens because their peers shared it. Peer pressure, status, social proof & belonging would seem their key motivations for sharing the video forward. TikTok on the other hand would see that same video shared because the idea mattered to the teens. In other words, they shared it because it was a 'great idea'.

What is a meme made of? It is made of inspiration.

- Dan Dennett

Creator bias

Finally, as platforms evolve their multiple sides they present new opportunities for users to interact. But in doing so, they need to straddle a balance between driving creation and consumption. Creation is a dynamic activity requiring creativity, effort and risk. Quality creation isn't easy. Consumption on the other hand is lean-back, passive, risk-free. Facebook has an overwhelming variety of ways to engage the user in consumption. But I fear features that drive creation may be getting a bit lost in the Facebook mix.

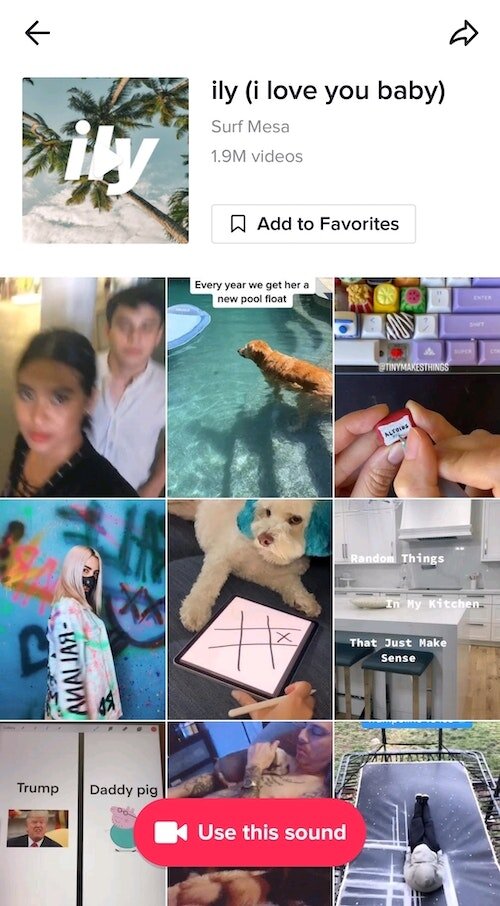

TikTok’s minimalistic, hyper-focussed and shallow design keeps the ‘add video’ button central, virtually begging the user to create. Clever features such as ‘Use this sound’ further emphasise and reward creation. After all, who doesn’t like to be in cool company? Such creator bias may underlie much of the popularity and power of this nifty app.