Why Societies Need Positive Persuasion

Many meaningful changes—whether personal or societal—start with someone shifting from maybe to yes. That shift often doesn’t happen by accident. It is the result of persuasion. Not coercion. Not deceit. Just people helping others do what’s in their best interest, sooner.

We often forget this. We assume persuasion is the domain of sales hacks or political spin. But the truth is: without ethical persuaders, our world would stall. Think about it—public health campaigns, civil rights movements, even getting your friend to open a savings account—they all rely on someone influencing behavior for the better.

Persuasion: The Hidden Engine of Collective Action

Let’s consider with some examples.

Public health. Most people wouldn’t have chosen to get smallpox inoculations in the 18th century—or COVID-19 vaccines in the 21st—without persuaders. Doctors, neighbors, even clergy stepped in not to force, but to frame: “This protects your family. Your community.” They shifted the focus from individual risk to shared reward.

Social change. When George Floyd’s murder sparked global outrage, the Black Lives Matter movement turned emotion into momentum. It wasn’t just hashtags—it was organizers turning protests into policies, and individuals persuading their workplaces, schools, and governments to confront systemic racism. Likewise, the #MeToo movement didn’t spread because everyone suddenly found their courage at the same time. It spread because one person spoke up, and others said, “You’re not alone.” Each story created space for another. That’s persuasion at scale—powered by truth, trust, and timing.

Personal habits. You probably didn’t start that workout routine, budget app, or plant-based diet because of the data overload in your app. You started because someone close to you said, “This helped me—you should try it.”

This isn’t manipulation. It’s persuasion rooted in empathy, credibility, and action. And it’s how movements grow from individuals to institutions.

Influence Isn’t Dirty—It’s Necessary

The term persuasion still suffers from post-war suspicion, amplified by Vance Packard’s The Hidden Persuaders and decades of media about cults and political operatives. But influence isn’t inherently shady. Its value lies in its application. Ethical persuasion is the connective tissue of a functioning society.

During COVID’s early chaos, public health professionals didn’t resort to fear-mongering. They livestreamed real ICU footage, explained vaccine science clearly, and shared messages like “do if for your family.” Local groups delivered groceries and organized check-ins. These weren’t manipulative plays; they were acts of trust-building, designed to unite society in a shared survival effort.

Now rewind to the early 1900s. Suffragists persuaded the public to expand voting rights for women using transparency, reason, and moral urgency. Marches, public testimonies, and legal arguments all built momentum for a social overhaul. That wasn’t a con job—it was clarity multiplied by courage.

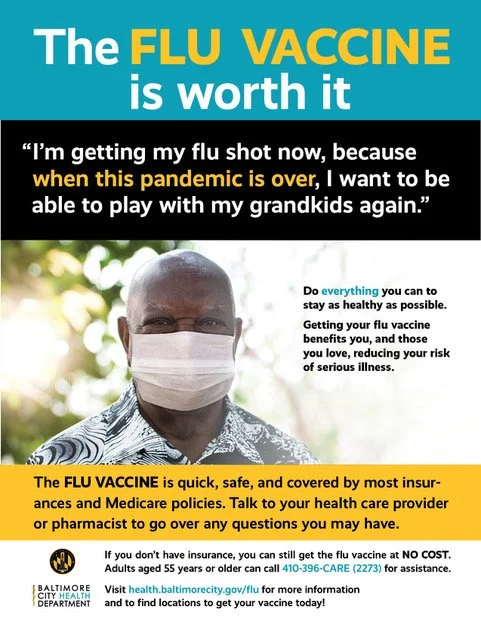

A persuasive public appeal from the city that gave us the epic ‘The Wire’.

Persuasion ≠ Manipulation

Contrast the above moments with Edward Bernays’s infamous 1929 “Torches of Freedom” campaign. Bernays hired elite women to smoke cigarettes in public, branding it as a feminist act of defiance against patriarchal norms. But the real motive? Boosting sales for Lucky Strike. It looked like liberation, but it was a profit scheme wearing the mask of progress—a textbook case of manipulation.

The confusion arises because persuasion shares surface tools with manipulation—emotions, stories, social cues. But their moral cores are worlds apart.

Take the movement to close the gender pay gap. It’s persuasive design in action:

Data is made visible through open salary spreadsheets and dashboards.

Consensus is built with ally pledges and #EqualPayDay campaigns.

Narratives shift as women take over company feeds to talk mortgages, security, and long-term impact.

This is persuasion with clarity, consent, and a goal that benefits everyone.

Product Design is the New Front Line of Persuasion

In today’s tech-driven world, product designers are the new persuaders. That’s a big responsibility. Design decisions shape behavior—and when done right, they help users do what they already want to do.

Headspace turns mindfulness into a low-friction routine. A soft “time to breathe” notification and a calming progress ring invite you back each day, but there’s no shame screen if you skip. The app’s persuasion lies in reframing meditation from a lofty discipline into a doable two-minute session—supporting the user’s own goal of mental clarity, not chasing endless screen time.

Airbnb leans on social proof without crossing into social pressure. When you see something like “Booked 4 times this week by travellers from your region,” it’s a credibility cue, not a countdown clock. Transparent fees and a 24-hour grace period keep the choice squarely in your hands. Because these messages are descriptive (how many bookings or views) rather than prescriptive (no ticking clock or “only 1 left!”), they serve as a credibility cue rather than hard-sell urgency.

Amazon’s “Customers who bought this also bought…” reduces cognitive load rather than creating FOMO. It surfaces accessories or replacements that pair with what’s already in your cart—an assistive nudge you can ignore, dismiss, or explore at will.

These features don’t manipulate. They guide. They respect. They’re persuasive because they’re aligned with user goals.

From Goals to Guardrails

When products are too well-designed—perfectly persuasive, frictionless, habit-forming—they can tip into overuse or even addiction. Think endless scroll feeds, autoplay videos, or notification loops engineered to hijack attention. These tools begin with the same persuasive intent as a good language app or budgeting tool: to help users follow through. But when success is measured only in engagement, the line between value and compulsion blurs. The same is true for human persuaders. History is full of charismatic leaders who began by rallying people for good—and ended by consolidating control, suppressing dissent, or distorting truth. Whether it’s a platform or a person, influence without limits becomes exploitation. Ethical persuasion must be paired with thoughtful guardrails—by design.

Above: iOS curbs phone overuse by baking Screen Time into the OS—and placing its widget in the left-of-home “Today” view by default. Daily pickups, app minutes, and quick-set limits are visible with a single swipe, turning mindless scrolling into a self-check you can’t entirely miss for long. Easy to override when needed, but hard to ignore, this widget is a good example of the quietly persuasive digital intervention - something we ought to see more of.